Why many Australians are paying at least 30c a litre too much for petrol

Updated

Photo:

Petrol prices were quick to rise after the drone attack, but have been slow in following the oil price back down. (ABC News: Alistair Kroie/Nicole Mills)

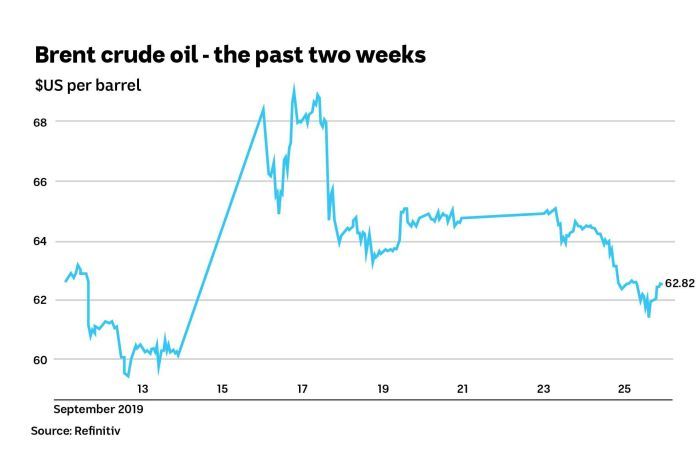

Less than two weeks after the biggest supply disruption in the history of the oil trade, global benchmark prices have gently settled back to where they were before the drone attacks on Saudi facilities.

The subtlety of the shift may be lost on most Australian motorists, who are still paying well above pre-attack prices.

In Melbourne, unleaded prices are still hovering around $1.60 cents per litre having peaked at $1.72 cents per litre in some service stations.

According to the ACCC’s “Petrol Price Cycles” data, the average Melbourne price was $1.30 a litre just before the squadron of drones set forth with the facilities at the Abqaiq and Khurais oil field in their cross hairs on September 14.

Photo:

Melbourne petrol prices soared as global prices rose, but haven’t tracked the oil price back down. (ABC News: Alistair Kroie/ FUELtrac/ACCC)

When oil traders scrambled to their computers on Monday morning after the weekend raid, the global benchmark (and the most important price on Asian markets) Brent crude jumped from $US60.25 a barrel to $US68.40 — the best part of 20 per cent higher.

It was still above $US69 a few days later, but has been on a downward trek ever since, as markets responded to soothing words from various Saudi “sources” saying production was coming back online more quickly than expected.

That message doesn’t appear to have filtered through to Australian bowsers as quickly.

Tracking why prices rocket up and tread warily down is a complex issue, made more difficult by the various margins and costs extracted between the oil well and cashier at the service station — along the way traders, the shipping lines, refiners, wholesalers and retailers all clip the ticket and finger pointing is a relatively easy way to deflect blame.

The big, vertically integrated energy corporations, capable of extracting a margin at pretty well every pit-stop along the way, can just throw their hands up and argue, “it’s the market”.

Traders’ margin

One of the great ways to make a quid on an Asian trading desk is to buy oil at cheaper Brent crude prices and sell at a Tapis premium.

It’s a financial engineering trick easily achieved by traders who never hold the physical commodity, but flip contracts around their screens.

Tapis is a thinly-traded, “sweet” low-sulphur fuel priced out of the Singapore market.

Its premium above Brent, which currently works out at 6 cents a litre at the pump, is commonly cited as a reason why Australian fuel prices are high.

Not everyone buys that.

The fact the Reserve Bank uses Brent rather than Tapis to track oil prices and their impact on the Australian economy tells you what it thinks is important, and to a large extent blows away the cloud of confusion caused by referencing Tapis prices.

Refiners’ margin

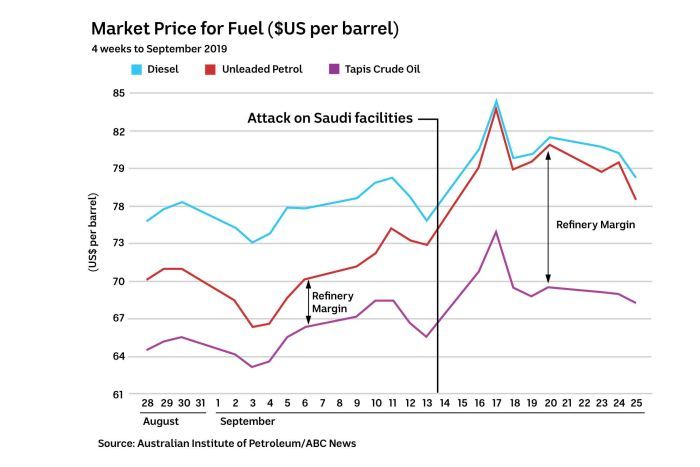

One phenomenon that is difficult to explain in the current cost spurt is the large expansion of the gap between the unrefined oil price and the refined fuel prices in Australia.

The gap could loosely be described as the refiners’ margin.

Using Australian Institute of Petroleum data (and yes, Tapis is its oil benchmark), the margin has expanded noticeably for unleaded fuel, but less so for diesel. The diesel margin was already pretty juicy.

Disruptions, such as the one in Saudi Arabia, can cause shortages in different pockets of the market, but what can be drawn from the recent unleaded margin expansion is refiners have very significant power and leverage over prices.

According to leading fuel analyst Geoff Trotter, while trading and wholesale margins have not moved much in the past two weeks, there has been a fair bit of action at the refining and retail parts of the pipeline.

Mr Trotter, the general manager of the hydrocarbon pricing intelligence business FUELtrac, says adjusting prices for currency, the refining margin contributed 2.5 cents per litre at the Australian unleaded pump before the attack.

After the attack, that has blown out to 7.5 cents per litre.

“The Australian dollar has not had a significant impact, it is all about the underlying margins being achieved at the refineries and retail level,” Mr Trotter said

“The oil companies have something of a windfall since the drone attacks, while motorists have suffered.”

Photo:

Refinery margins have widened noticeably since the September 14 attacks (Source: AIP/ABC News)

Retailers margin

Leading up to the attacks, the terminal gate price for unleaded fuel was around $1.29 per litre, while the price at the pump was in the low $1.30s — in other words a fairly skinny retail margin of 5-6 cents a litre.

Mr Trotter said not long after the drones hit, wholesale prices rose to $1.38 per litre while retail prices exploded, particularly in Melbourne, where they fell just shy of $1.72 per litre.

In Brisbane it just hit $1.78 at some outlets.

Given it was the same fuel that had already landed and was either at the terminal, or already in tanks under the service station, some pretty handy profits were booked on existing supplies.

“The retail margin went from a few cents a litre to more than 30 cents a litre in Melbourne, in Brisbane 42 cents,” Mr Trotter said.

Sydney, which operates on a different fuel price cycle, hasn’t seen those prices yet, but Mr Trotter says it is probably only a matter of time.

“The retailers move so quickly they can book that stock profit on what they already had stored, ” he said.

Fuel industry margins

| Gross Margins | Pre-attack (cents per litre) | Post-attack (cents per litre) |

|---|---|---|

| Trading | 6cpl | 6cpl |

| Refining | 2.5cpl | 7.5cpl |

| Wholesale | 7cpl | 7cpl |

| Retail (Melbourne) | 6cpl | 33cpl |

| Retail (Brisbane) | 6cpl | 42cpl |

Source: FUELtrac estimates Note: Values converted into the equivalent price of cents per litre at pump, Melbourne and Brisbane retail margins calculated on recent high points.

‘There are other factors’: retailers

BP, the only major retailer to respond to the ABC’s inquiry about the recent price rise, said its “aim is to always be competitive and attract customers to our sites”.

It depends on your definition of competitive.

Certainly dead heats can be exciting, but when every retailer moves in lock-step and discounting is only marginal, then the thrill for the motorist is somewhat diminished.

Websites and apps showing where and when to buy cheaper fuel:

“Generally speaking, the price at the pump is impacted by a number of different factors. In particular, international product prices and competition between service stations in a local area,” a BP spokesman responded in a written statement.

“There are also other factors including exchange rates, taxes and local operating costs,” the BP spokesperson added.

It is reasonable to point out, while there are around 1,400 BP-branded fuel and retail sites across Australia, 350 are owned by the company — the rest are independent businesses setting their own prices.

However, it is also reasonable to mention over the course of the past fortnight the Australian dollar traded in a reasonably narrow 1 cent band against the US dollar, the tax structure remained unchanged and so did labour costs.

The other big retailers, including Caltex and Viva Energy, owner of the Shell retail franchise, were unavailable or unwilling to comment.

What’s next?

The market is now weighing up security and supply issues against mounting pessimism about global economic growth and flagging demand for oil.

Respected global oil analyst Energy Aspects said the market remains deeply sceptical as to whether Riyadh’s claim of a “full return of oil production by end September” is credible.

It suggests expert analysis indicates damage assessment alone should have taken weeks and many spare parts may not be on hand for the repair job.

Energy Aspects estimates of the 5.7 million barrels a day (mbd) production — or 6 per cent of global supply — knocked out by the drones, between only 2.5 and 3 mbd is back online.

Big investment bank J.P. Morgan agrees, but says the impending US-China trade talks may be a bigger price driver in the near term. It’s betting the price will fall more.

“Oil sits at the low end of a three-year trading range of $US55/barrel to $US80/barrel despite multiple sources of supply stress — a 50 per cent cut in Venezuelan output, a 30 per cent drop in Iranian exports — the equally-impressive gains in US output [annual growth rate of about 1.3mbd] plus slowing demand growth,” J.P Morgan’s head of oil market research, Abhishek Deshpande, told clients.

“With signs of geopolitical tensions easing, tanker rates for key Middle East to Asian routes have declined and near-term call premium for Brent has also fallen,” he said.

“That said, while we continue to believe that Saudi supply will take closer to three months to normalise, the threat of further trade tensions and their knock-on effects to global growth and business sentiment could accelerate the weakness we observed in oil demand earlier this year.”

50/50 bet

CBA commodities analyst Vivek Dhar says the next significant shift in price is a “50/50 bet”.

“How believable is [the Saudi production recovery]? There are certainly incentives to push a positive story as the Aramco IPO (the partial stock market float of the Saudi oil industry) is not far off,” Mr Dhar said.

“What the Saudis have done has made it not so much a supply issue, but a geopolitical event.

“The focus will now shift to US-China talks as the key price driver.”

That means, according to Mr Dhar, that the geo-political focus is on further trade tensions, a slowing global economy and weaker demand.

CBA has the oil price slipping further to $US55-60 barrel range in the first quarter of next year.

Just don’t expect prices to fall as dramatically at the pump as they have risen in recent weeks.

Topics:

business-economics-and-finance,

First posted