Landfill legacy leads to recycling revolution

Posted

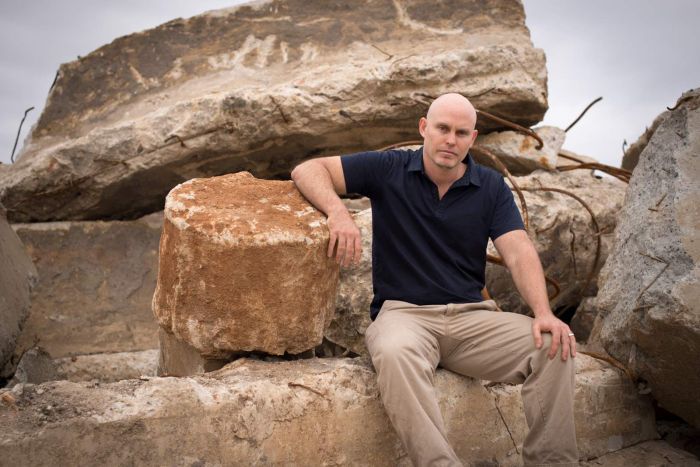

Photo:

Dan Hannagan digs concrete out of his family-owned landfill and breaks it down for recycling. (ABC Far North: Mark Rigby)

When Dan Hannagan took over the family landfill business he was shocked to discover just how much recyclable material is buried underground.

More than five years later, his site is one of the only privately owned dumps in far-north Queensland that recycles much of its waste.

Copper, aluminium, stainless steel, green waste and anything else of value is sorted and recycled on site, or sent away to third-party recycling agents.

Even slabs of concrete — some that have been buried for years — are broken down to various degrees and resold as road base, aggregate or sand.

Most significantly, Mr Hannagan recycles as much steel as possible to limit the amount of material going underground.

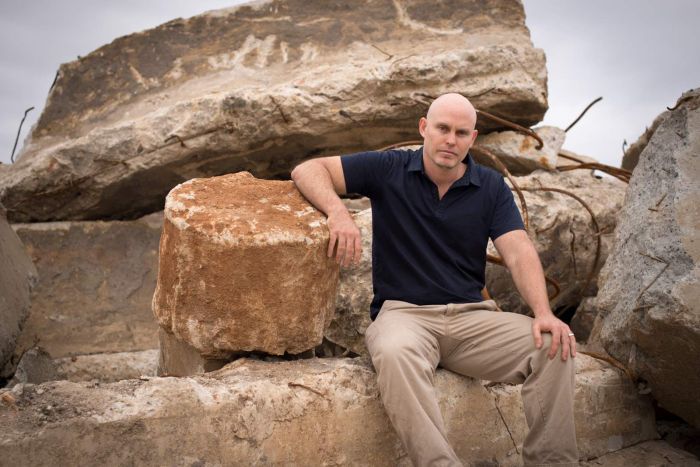

Photo:

Steel reinforcing bars are removed from concrete dumped and dug out of the landfill before they are sent for recycling. (ABC Far North: Mark Rigby)

“The scary thing is that at the current prices we don’t actually make any money [from it],” Mr Hannagan said.

“In 2008, when China was booming, steel prices were over $200 a tonne; they’ve been as low as $5 a tonne this year.”

The reality is there is little money to be made in any form of recycling, even if you own and operate your own landfill.

But as long as he is not losing money on recycling, Mr Hannagan said he felt obliged to do his part for the environment.

Photo:

Light-gauge steel is stored on site until a metal recycling company is able to bring an excavator and a baling machine to remove it. (ABC Far North: Mark Rigby)

“It doesn’t look good on the business plan, but I care about making sure that whatever I do here reflects on the future,” he said.

“I’m making sure I’m doing something for the next generation rather than just sticking it all in a hole.”

‘Like separating spaghetti Bolognese’

Mr Hannagan said the reason many other landfills avoided recycling materials was the difficulty of sorting waste once it was brought to site.

“It’s like spaghetti Bolognese; it’s very hard to separate the pasta back out, the tomatoes back out and the mince back out,” he said.

Photo:

Bales of light-gauge steel are stacked before being loaded onto a truck and sent away for recycling. (ABC Far North: Mark Rigby)

“Once [materials] come out on a truck or a skip bin and they’re piled up, it costs a lot of time and money to process.

“That’s why most other landfills don’t bother with recycling because it’s much more cost effective to just get a dozer and push it into a hole.

Even recycling household or domestic items could become cost prohibitive when it became contaminated with other materials.

“If you’ve got a cigarette butt in a beer bottle or an unwashed milk carton in a load of recycling, that load is spoiled,” Mr Hannagan said.

Photo:

Contaminants in a load of recycling can sometimes result in the whole load being sent to landfill. (Supplied: Luke Storta)

“You’re not going to pay someone an award wage to stand there and separate it out or clean thousands of bottles.

“[So] a good percentage of waste that’s sent to recycling facilities is too difficult to sort and it gets sent back to landfill.”

Australians are poor recyclers

Mr Hannagan said many Australians would be shocked to realise the nation’s recycling practices are years behind some other developed countries.

“You talk to Germans about [waste] and they’ll pull the staple out of a tea bag to put it in the metal [recycling] bin,” he said.

“Then they’ll open up the tea bag and that goes in the green waste bin and the rest of it goes in the paper bin — and that’s just how they live their life.

“It’s the same in Japan. They know that can goes in that bin, and that bottle goes in that bin, and they’ll take the labels off [because] it’s just become part of their culture.”

Photo:

Food scraps and other contaminants are notorious for ruining cardboard recycling. (Rebecca Brewin)

In order for there to be a shift in Australia’s recycling culture, Mr Hannagan believed there must first be an acknowledgement of the problem.

“A lot of waste isn’t getting processed, a lot of waste isn’t getting recycled and it’s ending up in landfills,” he said.

“Once people start to become aware of that then you’ll get a bit of public understanding.

“Hopefully that steamrolls or snowballs into a system where people start saying ‘Okay, I’ve purchased this, now I want to throw it out. What can I do with it?’.”

Photo:

Mr Hannagan said more people needed to be aware of what is and is not recyclable to effect any real change. (Supplied: Mildura Rural City Council)

Topics:

recycling-and-waste-management,