Did you know the US has 650 million barrels of crude oil stored under Texas?

Updated

Photo:

The United States is the world’s largest oil producer, but it is also the world’s largest oil consumer. (Reuters: Jessica Lutz)

The attacks on Saudi Arabian oil pipelines has cut the kingdom’s production output in half, reducing the world’s crude oil supply by five per cent, but US officials seem confident they can meet demands, even if it means drawing on the country’s huge underground oil stores.

Key points:

- The US has more than 640 million barrels of crude oil stored in four underground caverns

- Saudi Arabia is the world’s biggest oil exporter, shipping about 7 million barrels of crude daily

- The US produces roughly 12 million barrels of oil per day, but consumes 20 million

Iran has denied blame for the attacks that targeted the world’s biggest crude processing plant in Saudi Arabia and triggered the largest jump in crude prices in decades.

Amid a flurry of Twitter posts on Monday morning, US President Donald Trump assured his audience the United States had become such a big producer it no longer needed oil from the Middle East.

He also said he had authorised “the release of oil from the strategic petroleum reserve, if needed”.

“I have also informed all appropriate agencies to expedite approvals of the oil pipelines currently in the permitting process in Texas and various other States,” Mr Trump wrote in the Twitter thread.

But while the US is a massive oil producer, it still relies heavily on Gulf oil.

Here we look at how much oil the US currently produces and consumes, and how much they have in underground reserves.

Hidden underground US oil stores

Photo:

The US Strategic Petroleum Reserve currently holds more than 640 million barrels of crude oil. (Reuters: Richard Carson)

The US currently has 644.8 million barrels of crude oil stored in four underground salt caverns in the states of Texas and Louisiana, according to the Department of Energy.

This strategic petroleum reserve (SPR) — the world’s largest emergency supply of crude oil — was established in 1975 after Arab states cut-off supplies to the US in response to their support of Israel in the Arab-Israeli War, causing oil prices worldwide to skyrocket.

The oil crisis sent the US economy into recession, and the SPR was set up to mitigate any future damage from interruptions in the global oil supply.

According to the US Office of Fossil Energy, a US president can authorize withdrawal of crude oil “in the event of an energy emergency”.

The SPR has been used only three times — most recently in June 2011, when then president Barack Obama directed a sale of 30 million barrels of crude oil to offset disruptions in supply due to unrest in Libya.

The stockpile is sufficient to cover “the equivalent of 143 days of import protection”, according to the reserve’s website.

The stored oil is unrefined, so if it were to be released it would need to be processed into fuel before it could be used.

It also takes time to transport the oil from the caverns, meaning if presidential authority were given, it would take almost two weeks before the crude oil hit the markets.

The US still relies on Gulf crude oil imports

The technology-driven US drilling boom that started more than a decade ago has made the United States the world’s largest oil producer.

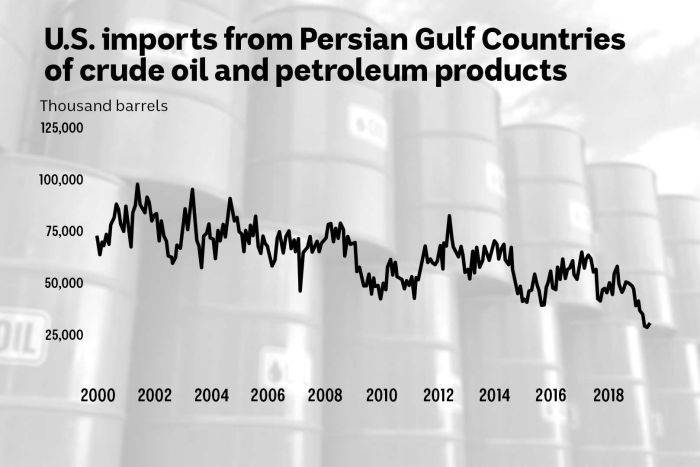

But it is also the world’s largest oil consumer, and last year imports of crude oil and petroleum products from the Gulf region still flowed in abundantly.

“By and large, we are still importing quite a bit and not totally immune to the world market,” said Jean-Francois Seznec, a senior fellow with the Atlantic Council Global Energy Centre.

Saudi Arabia is the world’s biggest oil exporter, shipping about seven million barrels of crude daily around the globe. The United States, produces roughly 12 million barrels per day, but consumes 20 million bpd, meaning it must import the rest.

Much of the US shortfall comes from Canada, but some still comes from Saudi Arabia, Iraq and other Gulf nations because several US refineries prefer their oil.

Crude oil is graded by density and consistency, and oil from different geographical locations will naturally have unique properties.

The biggest US refinery — Motiva Enterprises LLC in Port Arthur, Texas — is half-owned by Saudi Arabia’s state energy company, Saudi Aramco, and is set up for heavier Saudi grades.

Other refineries, particularly in California, are isolated from big US oil fields and must also rely on cargoes.

The mismatch between what US refiners want and what the United States produces means that in 2018, the US imported an average of 48 million bpm of crude oil and petroleum products from the Gulf region, according to the US Energy Information Administration.

That is down about a third from a decade ago, as domestic oil and gas production soared, but roughly the same level as in 1995 and 1996, according to the data.

Phillip Cornell, another senior fellow with the Atlantic Council, who used to advise Saudi Aramco, called Mr Trump’s claim that the US does not need Middle East oil “nonsense”.

But Sarah Emerson, president of ESAI Energy LLC, said the Saudi production outage, if it is prolonged, could provide an opportunity for US crude oil producers to expand their overseas markets.

How susceptible are US oil facilities to attack?

The recent drone attacks on Saudi Arabian oil facilities reduced the nation’s production by half, but experts said an attack of this size would be much more difficult to carry out against the US.

The United States has more of a geographic buffer than Saudi Arabia and lacks hostile neighbours, said Ben West, security analyst with the intelligence firm Stratfor.

The most vulnerable infrastructure, pipelines, can be repaired quickly, Mr West said.

“Even if there were an attack, it’s unlikely to knock out half the US oil and gas production,” Mr West said.

“I think Iran is much more likely to be able to successfully carry out a cyber attack than a cruise missile or drone attack, and it’s still an unlikely scenario.”

Amy Myers Jaffe, senior fellow for energy at the Council on Foreign Relations, said the US oil industry also had “a lot of redundancy”.

US refineries go offline often after accidents or storms, with little impact to the market, Ms Jaffe said.

Even production in the country’s biggest oil field, the Permian Basin in Texas and New Mexico, is spread across thousands of wells in a 194,250-square-kilometre region. The kind of gas-oil separation facility hit in the attacks in Saudi Arabia is done in smaller plants located across US oil fields.

“It’s pretty hard to imagine some group having people here and they’re going to fly a drone over the Houston Ship Channel or over Newark and somehow it’s not going to be noticed,” Ms Jaffe said.

“Could you knock out one company’s crude processing unit and throw them offline? I suppose. You’d have to go down to Midland, Texas, and get away with it.

“I would be more concerned about cyber vulnerability.”

Security for US energy infrastructure was tightened in the years following the September 11, 2001 attacks to include tighter inspection standards and better backgrounding and credentialing of workers, said Henry Willis, a senior policy researcher at the RAND Corporation.

“We do know that once someone figures out a way, others learn,” said Mr Willis.

“I imagine if you’re responsible for facilities security and you haven’t done it already, you’re assessing how you account for drone threats.”

Topics:

business-economics-and-finance,

First posted