Great Australian Bight deep sea survey discovers other-worldly marine life

Posted

Photo:

The survey’s data is the deepest systematic sampling of Australian waters. (Supplied: Marine Biodiversity Records)

With oil exploration looming on the horizon for the Great Australian Bight, stakeholders felt it was an important time to learn more about the species that call the rough waters off Australia’s southern coastline home.

In a joint effort between BP, The South Australian Research and Development Institute [SARDI], the CSIRO, the University of Adelaide and Flinders University, the Great Australian Bight’s deep sea waters have been surveyed for the first time and results have revealed 400 new species of invertebrates.

The paper’s lead author, Dr Hugh Macintosh, said this kind of survey was important because it established baseline knowledge about the environment.

“Decisions like [oil exploration] can’t be made when you don’t have any information about the local environment, and it was identified that we knew nothing about the Great Australian Bight,” he said.

“[We] were given free rein to design these studies, to go out and report back to government and industry stakeholders so that we could help informed decision making.

“All we can hope for is that people make these kinds of decisions with evidence so that people can weigh [up] those when they make these decisions.”

The study’s surveys took place over six years, between 2011 and 2017.

Since 2011, the Australian Government has awarded 11 exploration permits in the Great Australian Bight.

Norwegian oil company Equinor plans to drill an exploratory well on its permit site in late 2019, pending approval of its environmental plan from the regulator.

New species

The Bight’s waters are usually associated with the southern right whales that spend their winters migrating and calving in its waters.

This study shed light on the Bight’s unseen depths.

“The deep sea is fascinating — you find things with fangs, that glow, that have jelly — you find really weird, wonderful, alien creatures,” Dr Macintosh said.

“A lot of the stuff we found is typical for the deep sea, but deep sea species are really weird — there are giant sea spiders that roam the landscape, big sea cucumbers that are the consistency of Jell-o.

“My work is on clams. Clams usually eat plankton, but there isn’t a lot down there, so there are carnivorous clams that lie in wait to eat things that wander past them.”

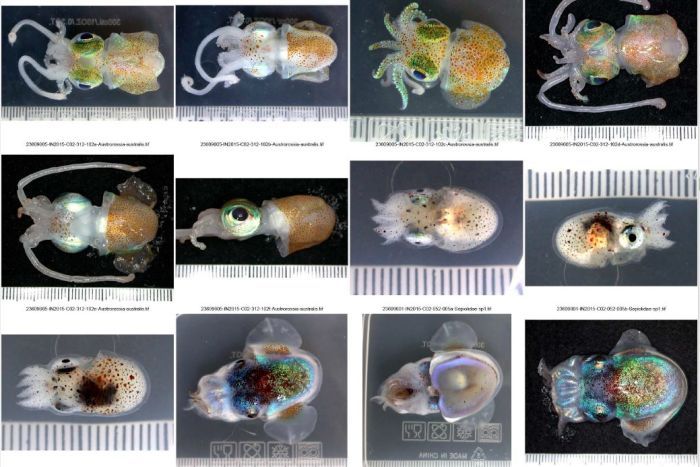

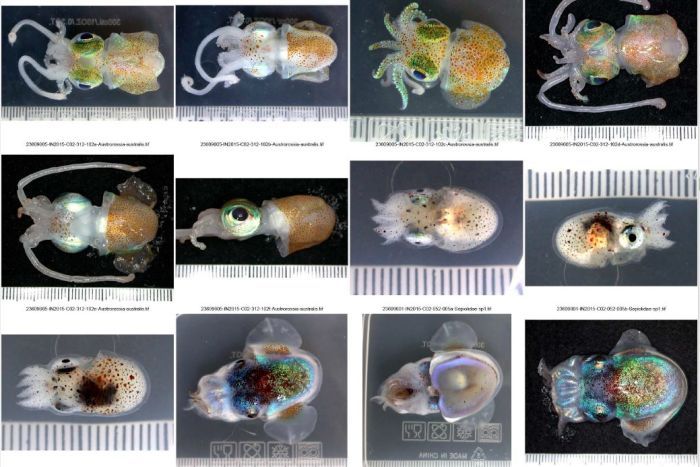

Photo:

The animals were photographed as soon as they were pulled from the water to preserve their shape and colour. (Supplied: Marine Biodiversity Records)

The study collected 1,267 species and 32 per cent of these were new to science.

“Finding new species is always fantastic,” Dr Macintosh said.

“But what I will say is every time you go out and do deep sea surveys of this magnitude, you actually find that similar percentage of new species.”

Dr Macintosh said that if similar research was done elsewhere, the results and the kind of creatures found would be similar.

“That’s one thing I like to point out — it’s interesting, but not surprising to us. It’s all fascinating and exciting because it’s all new, but it’s not necessarily surprising.

“The Bight is exceptional in just how big it is, how many fisheries it provides for — there is that large tuna fishery, large sardine fishery — it’s a nursing ground for whales and sharks.

“In those respects it is unique, but what’s interesting is that the Bight’s deep sea looks like the deep sea everywhere.”

Significant study of the deep sea

The study focussed on the marine creatures that live between 200 metres and 5 kilometres beneath the water’s surface — a depth of water that science knows comparatively little about in any of the world’s oceans.

“Ringing the coast of any landmass, you have an area called the continental shelf and it goes outwards from the beach and gets subtly deeper until it gets to about 200 metres below the surface, then that shelf drops off and the depths get deeper and deeper on a steep slope,” Dr Macintosh said.

“Eventually that peters out into what’s called the abyssal plain — which is about 5 kilometres deep — so we were looking from where the shelf ends to the start of the abyssal plain.”

Photo:

The study established a baseline for the Bight’s biodiversity, which will help scientists track the ecosystem’s health if oil exploration goes ahead. (Supplied: Marine Biodiversity Records)

This study was also the deepest ever water sampling in Australian history.

“It’s an area that we knew nothing about before this,” Dr Macintosh said.

“We know comparatively little about the deep sea but to be able to systematically survey this area and get an idea of what the habitat is like and how it relates to other deep sea areas in Australia, is significant.

“Sampling in the deep sea is really challenging. We went out there six times, using specially fitted ships and a variety of methods to sample these animals.

“We did a trawl, which is basically a big net. Sometimes it’s so deep it takes several hours for it to arrive at the sea floor.”

Collecting these specimens presents a unique challenges for researchers.

The transition from the sea floor to the surface, where it is pitch black, highly pressurised and only 2 or 3 degrees Celsius, kills most of the specimens.

“A lot of them are just very gelatinous and the collecting methods can damage them but even if they come up nicely, they really quickly start to fall apart into just ooze.”

Due to these constraints, the animals were photographed as soon as they were removed from the water.

The alcohol scientists use to preserve the specimens bleaches them and the photos help taxonomists with their later identification work.

“One of the things that’s been really impressive about this study is that we have had a really, really quick turn-around time from sampling to being able to report,” Dr Macintosh said.

Photo:

Without the high pressure compression of the deep sea, some of the specimens turned to “ooze” when they were brought to the surface. (Supplied: Marine Biodiversity Records)

It took eight months to identify all of the samples, which Dr Macintosh said is “lightning” fast for a study of this magnitude.

“It’s common for things to wind up on shelves collecting dust.

“But we put together a really good team of taxonomists. There are 30 co-authors of this paper.”

Studies independent of BP funding

“We had total independence in designing, going out, sampling, surveying, identifying and reporting. There was no pressure from any stakeholders,” Dr Macintosh said.

“And I think that’s what we should do more of: evidence-based decision making. [Stakeholders should] provide funding and resources that allow scientists to gather this kind of information, instead of being done in-house by industry.”

BP announced in 2016 that it would not continue with its exploration of the Bight but has continued to support the research program.

“Our contribution to the Great Australian Bight research project was an important part of the planned exploration program to further understanding of the region,” said a BP spokesperson.

“We believe that the research project will help build knowledge of the area and benefit many.”

Topics: